Grammar

Possessive clauses - what exactly is possession from a linguistic point of view?

In linguistics, we understand possession to be a relationship between two referents in which one owns the other. This can describe material possession relationships, for example, but can also refer to kinship relationships (my mum) or even body parts (your leg). Possession can be expressed by various means, e.g. word order, grammatical cases or possessive affixes. Various languages have a verb that denotes possession; in English this is to have. Many Uralic languages express possession through an existential construction though. In the following texts you can read how possessive clauses work in Uralic languages using the examples of the Samoyedic languages Nganasan, Enets and Nenets and the tungusic language Evenki.

Possessive clauses in Nganasan

The Nganasans are the northernmost inhabitants of the Eurasian area. Together with its close relatives Nenets and Enets, Nganasan forms the Samoyedic branch of the Uralic language family with contacts to Dolga and Evenki.

The INEL Nganasan Corpus is available for download under open access conditions and via the web-based search.

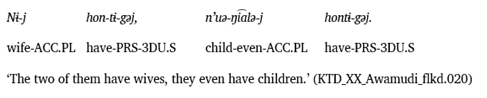

Nganasan is a special case among the Samoyedic languages. Here you will find both transitive possessive clauses with the verb to have and possessive constructions that are structurally similar to existential clauses. Let's first have a look at the habeo-verb: The transitive verb honsɨ to have handles possession, alingning with the subject in number and person. The possessor becomes the subject, while the possessed object stays in the accusative case.

Nganasan allows flexibility in expressing possession. The possessor does not necessarily have to be expressed lexically: the personal verbal ending referring to the possessor is often sufficient as seen in the previous example.

Nganasan also boasts another possessive verb, ŋuðasa to own, for alienable relations. The possessor controls the stable-time relation, emphasizing the existence of the possessive bond.

In negated possessive clauses, Nganasan brings in the negative auxiliary 'ńisɨ', followed by the verb honsɨ to have in the connegative form. This construction is more common in the past tense, but can also occur in the present.

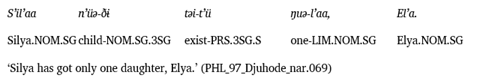

Another possibility in Nganasan is the existential type: In this type, possession is expressed through an existential construction. Nganasan uses təij 'to exist' and not the verb of being ij. In Nganasan, the possessor in these constructions can be expressed by the nominative form or, more rarely, by the locative form. In the case of a nominative possessor, the possessor is in the nominative form and additionally marked on the possessor by a possessive suffix, as can be seen in the following example.

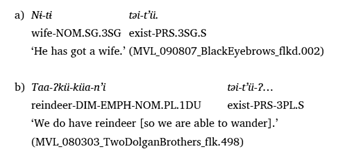

However, it is also possible that the possessor is not explicitly expressed, but only the corresponding possessive suffix refers to the possessor. This can be seen in the next two examples.

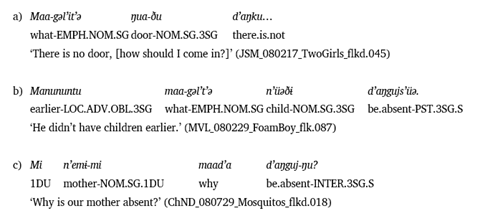

In Nganasan, the realm of negation in nominative possessive clauses is a nuanced landscape: the negative existential verb ďaŋkuj and the negative existential particle ďaŋku offer two possibilities: ďaŋku is common in the present tense and agrees with the subject’s number; for past, future or moods, the verbal construction steps in.

Possessive clauses in Enets

The samoyedic language Enets is spoken on the Taimyr Peninsula and its closest linguistic relative is Nenets. Enets can be divided into two varieties: Forest and Tundra Enets. These varieties are increasingly regarded as independent languages. While the speakers of Forest Enets are mostly located in the village of Potapovo and the town of Dudinka, Tundra Enets can mainly be localised in the village of Vorontsovo and in the Tukhard tundra. With currently fewer than 30 speakers who are fully proficient in Forest or Tundra Enets, both varieties are considered to be highly endangered.

The INEL Enets Corpus is available for download under open access conditions and via the web-based search.

Unlike Nganasan, Enets does not employ a habeo-verb and has, thus, no transitive possessive clauses. But Enets exhibits the same existential constructions as Nganasan when it comes to the expression of possession: the possessor is either in nominative or, again rarely, marked for locative.

Regarding the nominative possessive, two types emerge: one featuring the verb tɔneeš 'to exist' as its predicate, while the other, more rare one, operates without a verb. In both cases, the overt possessor takes the nominative form, and the possessed NP is marked with a possessive suffix. However, overt possessors are a rarity, as the context typically pinpoints their person.

(1) Ɛse-biʔ nɛ kasa-za tɔnee-š

F. father-NOM.SG.1SG woman fellow-NOM.SG.3SG exist-3SG.S.PST

‘My father had a sister.’

(2) Mɔreʔɔ kasa šize nɛ nʼe-za.

F. Moreo man two woman child-NOM.SG.3SG

‘The man Moreo has two daughters.’

(3) Ɔdo-baʔ tɔnee.

F. boat-NOM.SG.1PL exist.[3SG.S]

‘We have a boat.’

In Enets, this sentence type encounters negation via the negative existential verb (F. ďaguš, T. ďiguš 'to be absent'). This verb aligns its form with the number of the possessed NP, which, in turn, is marked with the personal possessive suffix.

(4) Xučii kunʼi-xuru pizi-za dʼagu.

F. cuckoo.[NOM.SG] how-INS nest-NOM.SG.3SG be.absent.[3SG.S]

‘The cuckoo never has a nest.’

Possessive clauses in Nenets

The samoyedic language Nenets can be divided into two major varieties: Tundra Nenets and Forest Nenets; Tundra Nenets is further divided into a western, a central and an eastern group.

The INEL project is working on all Tundra dialects as well as Forest Nenets. The eastern Tundra dialect, Taimyr Nenets, accounts for a large proportion of the INEL data. It is spoken in the western part of the Taimyr Peninsula and in the basin of the lower Yenisei, while Forest Nenets is spoken in the tundra and taiga zones along the Pur and Agan rivers and in the area of Lake Numto. In the last Russian census in 2010, a total of around 44,000 people stated that they speak a variety of Nenets, of which only around 2,000 belong to the Forest Nenets.

The INEL Nenets corpus is available for download under Open Access conditions and via the web-based search.

Both Tundra and Forest Nenets, much like Enets, don't exhibit a habeo verb. In Nenets, two other verbs play a role when it comes to marking possession: the existential verb and the verb of being.

Within the Nenets languages, possessors have the choice of two roles: they can appear in the nominative or the locative case. However, the nominative form is used more frequently. Possession can also be marked only with a possessive suffix attached to the possessive.

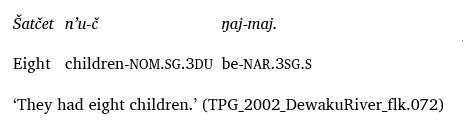

As already mentioned, possession in the Nenets languages is expressed with two central verbs: the existential verb (see the previous example) and the copula. This occurs when the possession is quantified, e.g. with a number.

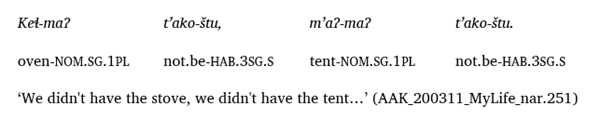

In Tundra and Forest Nenets negations in possessive clauses are expressed by using the negative existential verb, as can be seen in the following example.

Possessive clauses in Evenki

Evenki belongs to the northern group of Tungusic languages and is spoken by around 5000 people in the eastern part of Siberia. The area in which speakers of Evenki are found stretches north-south from the Arctic Ocean to the Chinese border of Russia and west-east from the Yenisei to the Pacific Ocean. In accordance with this large territory, Evenki is strongly divided into dialects; the larger dialect groups are North Evenki, South Evenki and East Evenki.

The INEL Evenki Corpus 1.0 is available for download under open access conditions and via the web-based search.

Evenki (as well as other Tungusic languages) expresses predicative possession similarly to Samoyedic. It manifests the “existential” type of possession, i.e. uses the ‘be’-construction with the Possessee in the Subject position (‘something is at somebody / of somebody’), (1).

(1) Tar Karaka-ji hunadʼ-i-n bi-ɦi-n!

that.[NOM] Karakan-ATTR.[NOM] daughter.[NOM]-EP-3SG be-AOR-3SG

‘Karakan has a daughter !’ ["Burujdak" (NNR) ] – lit. ‘his daughter (Possessee) is of Karakan (Possessor)’

There can be two sub-types of existential possessive constructions, depending on how the Possessor is marked. Both are attested in Evenki. The first one is the so-called genitive. In this construction, the Possessor is marked in the same way as in the noun phrase. The Possessor ‘I’ in (2) takes the attributive form (‘of me’). The Possessee (‘dried meat’) takes the dedicated possessive suffix signaling the person and number of the Possessor (1SG ‘my’).

(2) min-ŋi bi-hi-n təːli-l-bi

I-ATTR.[NOM] be-AOR-3SG dried.meat-PL.[NOM]-1SG

‘I have dried meat , let's go there!’ ["Fox and bear" (UV) [1928]] - lit. ‘my-meat is of me’

Exactly the same marking would appear in the corresponding noun phrase: min-ŋi təːli-l-bi ‘my dried meat’.

The Possessor can be overtly expressed, as in (1), (2), or omitted, as in (3). In this case, it is manifested only by the possessive suffix on the Possessee (‘my bread’, ‘my tea’).

(3) kləbu-n-mi bi-ži-n, čaj-u-ɣ-mi ačin

bread-ALIEN.[NOM]-1SG be-AOR-3SG tea-EP-ALIEN.[NOM]-1SG NEG.EX

‘I have bread , [ but ] I have no tea.’ ["The lost kettle" (NNR3) [1913]] – lit. ‘my-meat exists, my-tea does not exist’

The second sub-type of the existential possessive construction is locational, (4). In this construction, the Possessor is marked not as the modifier of a noun phrase, but as the Location. In (4), the Possessor ‘I’ takes the Dative/Locative case (‘for me, at me’). Note that, in contrast to the examples above, there is no possessive marker on the Possessee (‘horse’).

(4) Min-du muri-r kətə-kakun bi-ɦi-n-di!

I-DAT/LOC horse-PL.[NOM] many-AFCT be-AOR-3SG-EMPH

‘I have a lot of horses !’ ["Burujdak" (NNR) ] – lit. ‘many horses are at me (or for me)’

The negative predicative possessive construction in Evenki is structurally the same as the affirmative one. The dedicated negative existential ačin is used instead of the affirmative bi- ‘be’, (5), see also (3) above.

(5a) min-nʼi nʼadʼu-l-wị aːči-r

I-ATTR relative-PL.[NOM]-RFL.SG NEG.EX-PL

‘I have no relatives.’ ["Hares and wolverine" (KSh) [1930]] – genitive

(5b) min-du oron ačin

I-DAT/LOC reindeer.[NOM] NEG.EX

‘I have no reindeer .’ ["Sentences" (NNR2) [1912]] – locational

However, in Evenki, there is one more pattern of negative possession, which is more intriguing, (6). In this case, the negative existential ačin is accompanied by the copula ‘be’: in this combination it means something like ‘be without’. The Subject is the Possessor and not the Possessee: it is the Possessor that agrees with the predicate in person and number, ‘I am’ (not ‘it is’) in (6). The Possessee (‘sleeping place’) takes the accusative (indefinite accusative) case. Thus, instead of the structure like ‘something is not of me / at me’, here we deal with the structure ‘I am without something’.

(6) aːčịn aːnŋụ-nạ-jạ bi-ši-m

NEG.EX spend.night-PTCP.PRF-ACC.INDEF be-AOR-1SG

‘I have no sleeping place’ ["Heladan" (KSh) [1930]] – lit. ‘I am without sleeping place’

>> Русская версия

Посессивные конструкции эвенкийском языке

Сегодня мы завершаем нашу грамматическую серию на тему посессивных конструкций в уральских языках тунгусским языком, а именно эвенкийским. Эвенкийский язык относится к северной группе тунгусских языков, на нем говорят около 5000 человек в восточной части Сибири. Территория, на которой встречаются носители эвенкийского языка, простирается с севера на юг от Северного Ледовитого океана до российско-китайской границы и с запада на восток от Енисея до Тихого океана. В связи с такой большой территорией, эвенкийский язык разделён на множество диалектов; крупными диалектными группами являются северно-эвенкийский, южно-эвенкийский и восточно-эвенкийский.

Эвенкийский корпус INEL 1.0 доступен для скачивания на условиях открытого доступа и через веб-поиск.

Как и другие тунгусские языки, эвенкийский выражает предикативную посессивность сходным с самодийскими языками способом. Посессивность обозначается экзистенциальными глаголами, т.е. используется конструкция "быть" с посессором в роли субъекта ('что-то находится у кого-то / от кого-то')

(1) Tar Karaka-ji hunadʼ-i-n bi-ɦi-n!

that.[NOM] Karakan-ATTR.[NOM] daughter.[NOM]-EP-3SG be-AOR-3SG

‘Karakan has a daughter !’ ["Burujdak" (NNR) ] – lit. ‘his daughter (Possessee) is of Karakan (Possessor)’[LE1]

В зависимости от маркировки посессора, существуют два подтипа экзистенциальной посессивной конструкции. Первая возможность - это так называемый генитив, где посессор обозначен так же, как и в номинативной фразе. Посессор 'I' в (2) принимает атрибутивную форму 'of me'. Посессивный объект ('dried meat') дополняется соответствующим посессивным суффиксом, который указывает на лицо и количество посессоров (1SG 'my').

(2) min-ŋi bi-hi-n təːli-l-bi

I-ATTR.[NOM] be-AOR-3SG dried.meat-PL.[NOM]-1SG

‘I have dried meat , let's go there!’ ["Fox and bear" (UV) [1928]] – lit. ‘my-meat is of me’

Точно такое же обозначение появится в соответствующей именной группе: min-ŋi təːli-l-bi 'моё сушеное мясо'.

Посессор может быть выражен открыто, как в (1) и (2), или опущен, как в (3). В этом случае на обладание указывает только посессивный суффикс у обладаемого ("мой хлеб", "мой чай").

(3) kləbu-n-mi bi-ži-n, čaj-u-ɣ-mi ačin

bread-ALIEN.[NOM]-1SG be-AOR-3SG tea-EP-ALIEN.[NOM]-1SG NEG.EX

‘I have bread , [ but ] I have no tea.’ ["The lost kettle" (NNR3) [1913]] – lit. ‘my-meat exists, my-tea does not exist’

Второй подтип экзистенциальных посессивных конструкций - локатив, (4). Здесь посессор обозначен не как модификатор именной группы, а как место. В (4) посессор ("I") находится в дательном/местном падеже ("для меня, у меня"). Обратите внимание на отсутствие посессивного маркера у обладаемого ('horse').

(4) Min-du muri-r kətə-kakun bi-ɦi-n-di!

I-DAT/LOC horse-PL.[NOM] many-AFCT be-AOR-3SG-EMPH

‘I have a lot of horses !’ ["Burujdak" (NNR) ] – lit. ‘many horses are at me (or for me)’

Отрицательная предикативная посессивная конструкция структурно такая же, как и утвердительная в эвенкийском. Ačin используется вместо утвердительного bi- 'быть', (5), см. также (3) выше.

(5a) min-nʼi nʼadʼu-l-wị aːči-r

I-ATTR relative-PL.[NOM]-RFL.SG NEG.EX-PL

‘I have no relatives.’ ["Hares and wolverine" (KSh) [1930]] – genitive

(5b) min-du oron ačin

I-DAT/LOC reindeer.[NOM] NEG.EX

‘I have no reindeer .’ ["Sentences" (NNR2) [1912]] – locational

В эвенкийском (6) есть и другая модель отрицательного обладания: отрицательный экзистенциальный показатель ačin сопровождается копулой 'be', что означает 'быть без'. Здесь субъектом является обладатель, а не обладаемое: обладатель согласуется в лице и числе с предикатом 'I am' (а не 'it is') в (6). Обладаемое находится в (неопределенном) винительном падеже. Вместо структуры предложения типа "что-то не от меня / на мне", предложение строится так: "Я без чего-то".

(6) aːčịn aːnŋụ-nạ-jạ bi-ši-m

NEG.EX spend.night-PTCP.PRF-ACC.INDEF be-AOR-1SG

‘I have no sleeping place’ ["Heladan" (KSh) [1930]] – lit. ‘I am without sleeping place'

Comparative view of the languages of the INEL project

In addition to The Year with the Forest Nenets, you can find a more detailed overview of the concept of dividing a year into months across all languages of the INEL project using the example of the month of April.

The concept of months is not the same in all languages, which makes translation even more complex. In many cultures, the transition between months is not tied to astronomical events, instead the months derive their names from recurring natural phenomena. This approach means that there are no fixed calendar dates for the beginning and end of months, and the lengths of months vary accordingly. Within communities, one and the same period can have several names, which illustrates the linguistic diversity.

- Enets

- According to Andrey Shluinsky's field research documents, the Forest Enets refer to this time of year as "lʼibi dʼirii", which means month of the eagle.

- In Helimski's Enets dictionary we see that the Tundra Enets call April "nazi iriɔ", which is the month of the reindeer calf. As we have already mentioned, the time period is not as fixed as the naming of the month in other languages, so this could also refer to May.

- Nenets

- Among the Forest Nenets, according to one source, April is the month of the crow: waɬnʼi tʼiɬʼi.

- Nganasan

- As you can read in the grammar of our project PI Beáta Wagner-Nagy, the Nganasans use different terms for the time around April. Most importantly, the 2nd half of March to the 1st half of April is called toruľi͡a kičəðəə the month of the reindeer calf.

- April is also known as ńerəbtəiɁ toďüɁ kičəðəəə month of the newborn reindeer.

- It can also be called noruə kičəðəə, which means month of spring.

- Dolgan

- In Dolgan, reindeer are also involved in the naming of the month of April: taba emijdiir ɨja - month of reindeer lactation.

- Evenki

- In Evenki, the dialectal differences result in a rather complex picture. In most dialects, April can be referred to as turan time, when the crows come back (turakī "crow"); in some dialects, however, this refers rather to March.

- Another expression is owilasa (Nepa) ~ owilahani (Tungir-Olekma) ~ owilaha (Amur-Bureya) ~ owin (Ayan): Time of ice crust (owin 'ice crust over snow (in spring)'); however, in some other dialects this expression is not used for April, but for May.

- Other dialects use the same concept, but it is a different lexeme: čēgalahani (Tungir-Olekma, Barguzin): Time of ice crust (čēga 'ice crust over snow').

- In addition to the mentioning of snow, we also find terms such as tiglan (Chumikan): Period of river opening (melting).

- Of course the reindeer can play a role in naming a period of time: šōnkān (Chumikan): Time of (reindeer) breeding (sōnŋā~šōnŋān~sōnŋāčān 'newborn reindeer'); in some other dialects it means rather May - this one is close to the Tundra Enets and Nganasanen!

- And finally, in Evenki it is also possible to say bilən (Ayan): month of the wrist (bilən 'wrist').

- Kamas

- In Kamas, the month is named after the Siberian chipmunk (Tamias sibiricus): it is the month of the chipmunk hunt (nʼăga 'Tamias sibiricus'; nʼăgaj 'to hunt Tamias sibiricus'; nʼăgaj-zən 'month of the chipmunk hunt').

The naming of the month or periods that roughly correspond to April in the languages of the INEL project essentially boils down to three terms:

- there are some languages that use the arrival of birds as a reference: the crow month in some Evenki dialects and in the Forest Nenets, while the Forest Enets refer to the eagle.

- reindeer and their life cycle also play an important role in naming: calves are born in spring and name this period in Dolgan, Nganasan, Tundra Enets and some Evenki dialects.

- some Evenki dialects use snow or the melting of snow as a reference point.

Even if where you live the snow has already melted and you don't have any reindeer babies around, hopefully you had a nice spring month!