Doing Research from the Home-Office: Reflections on the Potentials and Pitfalls of an Involuntary Turn to the Digital in Pandemic Times

INTRODUCTION: A BUMBY RIDE IN RETROSPECTIVE

Travel restrictions and lockdown measures hit hard from when the COVID-19 pandemic first reached Germany from March 2020 onward. As many other students and researchers at that time, I first intended to go along with online classes, zoom meetings and other digital measures as second-rate options to draw on while hoping to sit this one out and getting back to preparing my real fieldwork planned for my MA thesis as quick as possible. As we all know, this wish has gone unfilled in every way imaginable, yet, thanks to several instructors, co-workers and fellow students who reacted and adapted quickly to the unpreceded situation, the past two years also presented an unexpected opportunity to reflect more deeply on what the craft of doing ethnographic research as a practice is about.

This working paper presents a reflection on these exact challenges faced throughout the past two years when trying to plan, draft and execute research for my MA research project on the lived experience of the COVID-19 pandemic as a global crisis in Brazil. It hence reflexively engages with the circumstance that the research process itself became impacted by the same global crisis it was seeking to generate knowledge about, thereby leading to an involuntary turn to the digital when on-site field work became infeasible due to pandemic travel restrictions.

Throughout the following pages, I will lay out first, how the limits imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic developed the turn to the digital from a second-rate choice into a valuable “surprise” from where to “start looking” (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 30f). Second, the paper particularly addresses experiences of “failing” in the field (Kušić and Záhora 2020, 3) when attempting to generate knowledge through the digital and lay bare how I coped with them along the way. I then, third, elaborate on how I have found (other) ways to my field and fourth, present the methodological framework that emerged out of these lived experiences of doing research in pandemic times and how I put these ideas to work through an abductive hashtag analysis of the lived experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Lastly, I provide some concluding thoughts on what to take away from these reflections for future research concerning the potentials and pitfalls of generating knowledge in, through and about the digital.

1. THE DIGITAL AS A SECOND-RATE CHOICE? REFLECTIONS ON DISADVANTAGES,

LUCKY CIRCUMSTANCES AND PRIVILEGE WHEN DOING RESEARCH FROM THE

HOME OFFICE

Even though the turn to the digital has sparked ethnographic researchers’ interest for some time already, established as well as still emerging fields such as Digital Anthropology (Miller 2018), Virtual Ethnography (T. Boellstorff 2008) and Digital Media Studies (Coleman 2010) usually produce knowledge presupposing a priorly established interest and commitment to the digital in relation to one’s field of study. The external shock of the encompassing lockdown measures from March 2020 onwards, however, involuntarily confined the academic community as a whole to the home-office – ready or not.

PhD candidate Chiara Cocco, who reflected on the issue early after lockdown measures limited her plans of doing on-site research in 2020, described her experience in a blogpost as suddenly being cut off from “the body, the touch and the feeling” of usual real-life fieldwork (Cocco 2020). Yet, as she also contends, as much as it limited choices throughout the research process, the external shock of this unpreceded situation also forced ethnographers to “embrace the unexpected and reflect on it” (ibid.). Besides giving me a great deal of comfort knowing that I was not the only young researcher getting nowhere – in a very literal sense – Coccos’s contribution also presented one of many instances that inspired me to dig deeper into the epistemological rollercoasters this challenging situation held to explore.

First and foremost, as within my research project I was following the double hermeneutic approach (Guzzini 2000; Jackson 2011; Lynch 2014) that commits to a recursive and abductive logic of reasoning, constantly moving back and forth between concepts and the “experience of data generation” (Kurowska and de Guevara 2020, 1215), I considered myself a part of the hermeneutic circle – a perspective which encouraged me to start looking from my own positioned knowledges and continuously widen the orbit by letting myself be carried away – or abducted – by the data and surprises in the field that I encounter along the way (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 30f). I hence came to realise that research has never been nothing but a chain of second choices. Therefore, granting the messiness of fieldwork (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 38) its rightful place in the final product – namely the writing up – of the research endeavour became clear as an important pillar of what Schwartz-Shea and Yanow have called designing for trustworthiness (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 91-114) as laying out the whole research process transparently for the reader to decide how much sense to take away from it. I will do so here by subsuming my experiences[1] concerning the cognitive, physical, and financial effects of the pandemic situation throughout this past two years under the three main points of a) disadvantages, b) lucky circumstances and c) privilege [2]:

- The notion of disadvantage might be the most obvious association coming to mind when looking back at the sudden limitations put upon us seemingly overnight from March 2020 onwards. Seminars were hastily adjusted to an online format which revealed immense differences in the varying abilities but also available resources of instructors and students alike. Spending 45 minutes in the Zoom waiting room before waiting a little bit more for the teacher’s kids (or in one case a granddaughter) to unmute the microphone became a frequent occurrence. While some formats managed their forced jump to online teaching more smoothly than others, a general sense of unpreparedness persisted. However, us students on the other side, were not ready for the digital university neither. While the assumption of a digital natives narrative at first presumed us flourishing through the opportunities of attending seminars comfortably from home (Burns and Gottschalk 2020), the picture looked a lot different in practice. In my case, I had just started my MA studies at the Latin American Institute in Hamburg in October 2019 while writing up my Bachelor thesis simultaneously during the winter semester 2019/20. As irony has it, my BA certificate was issued on the 12th of March 2020, exactly four days before Germany went into its first lockdown. I therefore dived from the social isolation of the final desk phase of one academic endeavour right into the next.

Apart from the disappointment of not actually getting to get back to university life per se, which I was most excited about after I had just put the weight of my final BA grade off my back, the involuntary turn to the digital definitely affected me cognitively as in how much I was able to take away from my seminars compared to the presential teaching I was used to. First and foremost, a continuous sense of impersonality was hard to overcome when discussing contents online. Yet, it was not just the two-dimensionality of the interactions but the small details of academia’s social arenas that I had largely taken for granted until having been condemned to the home office by the pandemic restrictions. Small details that include the short chats prior to and after class but also the way to the campus itself – getting ready before, leaving just on time to catch the next bus after the one you had initially planned for, calming my thoughts during the bus ride, reorganising my playlist when changing lines and finally sorting my notes and going through some highlighted paragraphs of the preparatory texts while waiting for the class to start. As I realised during the course of the semester, this extra hour of being on the way presented an important ritual for me to cognitively locate myself in the setting of an academic exchange as of corporally arriving as well as leaving the social arena of the classroom. Simply switching this setting on by logging into a zoom session was just not the same. And as I interpreted from the frequent becoming practice of half or more of the participants turning off their camera during class, I was not the only one. This made social interaction and henceforth the exchange of ideas very challenging. Especially group works in constellations that exclusively came to be and were carried out online became difficult due to a lack of communication, commitment and sometimes sheer motivation. All in all, the pandemic circumstances did have a toll on my learning capacities and demanded an disproportionately large amount of work being done in isolation, henceforth expecting a maximum of commitment, and self-organisation while cutting off all the fun parts of being a student of interchanging ideas in class, during lunch and between afterhours drinks and rooftop talks.

With the pandemic waves coming and going throughout 2020 to 2021, the digital semesters also began to affect me physically, as I developed migraines which were traceable to muscle hardenings in my back – symptoms which (as I came to learn from the orthopaedist of my confidence) had become a frequent phenomenon related to too many hours of two-dimensional zoom conversations. Further, while never having had any issues with my sight, in 2021, the excessive screentime took another toll on me as I needed to start wearing glasses. However, once detected, these issues were relatively easy to handle with keeping the right physio therapist and optician on speed dial, I still got off relatively easy. A lot harder to shake off, by contrast, were the unstable funding conditions and the resulting planning insecurities concerning the final phase of my master studies.

While brushing off once-in-a-while connection problems and sounds of the refurbishments in my neighbour’s apartment, the financial funding of the last part of my MA studies which would have consisted in a semester abroad and a fieldwork stay of several month in São Paulo, Brazil, became a particularly challenging project. As the health situation impaired, sending institutions all over the world, including the University of Hamburg, famously called their students back home and enacted travel restrictions which prevented any further attempts of studying abroad other than connecting to the time zone of a host university’s seminar on Zoom throughout 2020. I hence decided to wait and apply for the winter term at the University of São Paulo (USP) in August 2021, a plan that also had to be further compressed to a fieldwork stay of three months from October to December that year, for which I managed to secure funding. However, due to the pandemic uncertainties, my funding institution decided on the condition that grants would only be disbursed after the actual research stay as well as reserving themselves the right to request me to return ahead of schedule, in case the health situation should impair again. On these shaky grounds, the realisation of the fieldwork became financially impossible as these conditions would have meant for me to have the money for the planned project at hand in advance – which I did not – as well as to quit my job and rent my apartment without any securities whether I might would be requested to return before the provisioned end date of my project and hence would not even receive the full funding as a reimbursement.

Taking it all together, my master studies during the pandemic restrictions were cognitively, physically, and financially challenging times. Yet, it is important to acknowledge that throughout these months, I also found myself within some simply lucky circumstances and recognise the fact that I faced these challenges from several very privileged positions to which I will turn next. - Despite all obstacles, there were also simply lucky circumstances that helped me stay focused and advance my academic plans throughout the constant need for rearrangements of expectations, objectives, and research interests during the past two years. First, even though the sudden turn to digital teaching overburdened many instructors and also us students at first, I perceived an unprecedented engagement to cope with the situation at hand. Throughout the summer term 2020 I hence was able to take part in a variety of seminars, colloquia and lectures that engaged directly with the external shock that had hit the university’s modus operandi so abruptly. The so gained insights, considering the effects of digitality in all sorts of topics that did not previously incorporate the subject, was despite all zoom fatigue also a cognitively enriching experience that I was only able to make by accident through the pandemic restrictions leaving no alternative.

A second lucky circumstance also directly equilibrates its negative pendant discussed above. While the long hours of screentime did leave their mark on my physical health, yet once having recognised this risk, the timesaving conditions of the remote classes also gave me the opportunity for planning additional work outs in my timetable which I would not have been able to cope with if all my daily activities would have required me to be there. Further, I was able to reconnect with people I have been practising with on a daily basis before my studies all over the world. This was a particularly beautiful experience as it re-established an actual sense of co-presence on the one side but also introduced very helpful routines and structures which helped me to stay focused and start my working days with a fresh mind on the other. Relating to the as cognitively challenging perceived experience of impersonality during the zoom sessions of university seminars discussed above, I would like to add the observation that at first, those of us taking part in the online trainings also logged in just on time for the practice to start. Yet, with time, we accustomed to either entering the virtual room a little early or taking five to ten minutes at the beginning for simple small talk. This made a huge difference for me, as I perceived social interactions in the academic as well as work context throughout the lockdown restrictions to remain rather pragmatical and target-oriented. Yet, most importantly, having a fixed commitment every morning at 9.00 am helped me to uphold structure in my days and therefore gave me valuable routines which I could hold on to and draw strength and motivation from for the sometimes very tiring hours of online classes after. This lucky circumstance hence helped me to maintain my physical but also my mental health throughout the past two years.

The third lucky circumstance to mention concerns my employment situation and hence the degree of general financial security I was able to enjoy during the pandemic. Until the end of February 2020, I was mainly working as a self-employed instructor for dance and Capoeira and took on occasional day jobs for students at catering-events. While still writing up my BA dissertation, I was looking for a more stable employment, preferably a desk-job which would allow me to also put some of the insights from my studies in Political Science to practice. I was already involved in several projects with the small registered association Beyond Borders e.V. in Hamburg, with whom I organise international youth exchanges with a focus on art projects, performing arts in particular until today (Beyond Borders e.V. / Projekte 07/09/2022). Yet, not until very recently, this work was completely unsalaried. Nonetheless, I really liked the work and grew keen on the idea of gaining more insight and experience in the field of non-profit organisations. Again, just by pure coincidence and therefore outrageous luck, fate had it that I signed my first contract as a working-student with the NGO Plan International Deutschland e.V starting on the 1st of March 2020 (Plan International Deutschland e.V. 07/09/2022). Even though I had to work from home after my very first two weeks in office and therefore encountered similar challenges to those I discussed in the case of online teaching, I was safeguarded from the immense wave of jobs lost due to the pandemic restrictions (Tagesschau 04/24/2021)– which many of my fellow students faced at that time. To complete this lucky streak, I further joined the chair of Political Science and Global Governance later that year in July, an opportunity that allowed me to experience the daily practices of academic teaching and doing research in situ, so to speak, without which I most likely would not have thought of pursuing an actual academic career after my MA studies as I am doing now. - All in all, it is therefore crucial to acknowledge the immense amount of privilege because of which I was able to cope with the discomforts and challenges related to the pandemic restrictions. I benefited cognitively as I had the luck to maintain secure employments that allowed me to explore the interfaces between academia, societal commitment, and activism. All of which did not only provide me with the means to reliably pay my rent but also held vital opportunities for professional exchange and networking practices which I benefitted highly from, for example, in terms of receiving first hand feedback on work-in-progress papers for my studies from much more experienced colleagues. Further, all my tasks permitted me to work from home and largely let me oversee my own time management between my studies and working hours. The fact that, within my living situation, I had a separate room with a stable internet connection to work and practice in available, also represents a privilege in itself which positively affected my learning capacities throughout the past semesters. These same basic conditions directly relate to and also interrelate with the physical and financial effects discussed above. The possibility to reconnect with my old Capoeira group from Spain and maintain my own dance classes via zoom did not only help me to work against a spinal column slowly bending under the pressure of solely two-dimensional screentime work, it also re-established a regular co-presence and healthy routines which helped me to start my desk work after practice with a fresh mind and hence played a crucial role in maintaining my physical as well as my mental health during the involuntary turn to the home office. Again, this benefit also rested on the condition of me having a suitable space with the necessary requirements at my disposal in the first place, which, of course, interrelates with a relatively stable financial situation that, as laid out above, mostly came to be on the grounds of outrageously lucky circumstances.

That being said, I will now turn to what kinds of conclusions I was able to draw from these experiences in a methodological manner. Or, abductively speaking: How the ongoing state of uncomfortable yet not existentially threatening working conditions allowed for a range of surprises which sparked fruitful reflections on what it actually meant to generate knowledge in pandemic times. However, this turn to the digital as a field of investigation has presented everything but a quick fix for the pandemic circumstances of my research project. Next, I will therefore lay bare how the surprises I have come across have been rather painful than pleasant, but always presented valuable opportunities to reflect on my own ways of doing research and pushed me to commit to the messiness of fieldwork (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 38) and compell myself to the unexpected and reflect on it (Cocco 2020).

2. A VICIOUS HEMENEUTIC CIRCLE? FACING FAILURE IN THE FIELD AND THE

OTHER MAIN CHALLENGES

[…] a passerby […] sees a drunk looking for his lost keys under a street lamp. Wanting to be helpful, the passerby asks the man where he dropped his keys. When he points to a place at some distance from where they are standing, the passerby asks him, with some surprise and consternation, why, then, he is looking over here. Here is where the light is,” the drunk explains, pointing to the overhanging lamp (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 30f).

This short anecdote drawn on by Schwartz-Shea and Yanow in their methodological monograph interpretive research design: concepts and processes (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012) has honestly helped me through a lot of nerve-racking moments during the past year. Yet, while interpretivist approaches in other disciplines like anthropology or sociology quite often dedicate a fair amount of their writings on possible challenges encountered when trying to construct, enter or immerse within their chosen field of study (Ungbha Korn 2019; Abidin and de Seta 2020), the messiness of fieldwork has long presented an unjustified silence in scientific writing, especially in the field of Political Science and IR (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 38) as of auto-ethnographically engaging the experiences of the researcher in the final written product of the research project and addressing moments of “failure in the field” and how to cope with them (Kušić and Záhora 2020). This part, hence, seeks to openly address the fact that the making of my MA thesis has been a story of constant re-writes, edits, impossibilities and second-rate options. Or, let me rephrase this: It was what research always has been but what barely gets its mentioning in the final end product: a mess. A mishmash of thoughts that we somehow manage to make sense of until a certain date and within a certain wordcount. Or, let me rephrase that again: It was knowledge-making at its best.

After gaining confidence about the digital as an opportunity to explore otherwise overseen aspects of my topic, my enthusiasm quickly became damped again when intending to put all the deep reflections and so innovative seeming ideas into practice. I shall elaborate on these experiences of failure below which, for a better overview, I will group in first, technical, and second, ethical challenges as well as lastly, concerns of a remaining good guys bias which had me running around the hermeneutic circle for a while until slowly finding ways how to deal with these perceived limits and treat them as “productive ruptures” (Bliesemann de Guevara and Kurowska 2020) on the way to this MA thesis how it finally came to be.

First, I quickly ran into very simple technical barriers as, for example, I forgot that my Brazilian SIM Card, through which I had access to a number of different WhatsApp groups, had gotten deactivated since I last used it in 2019. However, I also noticed that I wanted to find ways out of my own filter bubble yet preferably without messing up the algorithm for my private communication channels. I quickly thought about asking a friend from Brazil to send me a new one to use with a separate mobile phone, but then decided against it. Looking back, this might have been worth the effort as I then decided to set up two fake accounts on Facebook to immerse myself in the algorithmic paths down the rabbit hole (more on this in part 4) which both got blocked several times and also led to myself being permanently locked out of my own account probably due to all of them being registered with the same phone number. I probably could have explored social spaces evolving through private channels like Whatsapp and Telegram groups more, as studies on the populist communication strategies of President Bolsonaro had shown that a large portion of the misinformation spread took place under the public radar through private chat groups (Pereira, Bojczuk Camargo and Parks 2022). However, besides central ethical concerns (which I will lay out in more detail below) I felt a lot more comfortable with conducting my digital immersion experiences in pre-defined time blocks of about thirty minutes to maximum an hour a day on my laptop, particularly to allow me time to take a step out of the field which would have probably been more difficult with frequently ringing notifications in between. Further, as quick as I got excited when starting to explore the wide range of promising possibilities that Big Data approaches to Social Media research had to offer (Highfield 2015; van Haperen, Nicholls and Uiter 2018; Pournaki, et al. 2021;), my enthusiasm also calmed down just as fast when discovering that most features like the full archive research on Twitter were not accessible as an undergraduate student and further, that many tools like the CrowdTangle feature of the Meta (formerly Facebook) platform needed to be applied for without any transperancy on what grounds an access would be approved or denied upon (Shiffman and Silverman [Meta] 2020).

Second, ethical concerns also arose when intending to construct my field from the inside. For instance, with my German number, I was still part of the family chat of my Brazilian life partner, which frequently contained a number of highly relevant seeming insights, yet it did not feel right to draw on these inputs which sometimes sparked controversial discussions on the topic. I did write down some thoughts on these interactions in my research diary but refrained from taking screenshots or the like – as members would share their content in the assumed privacy of a WhatsApp chat and there was just no way imaginable for me how to get anything close to asking them for their informed consent to draw on their posts for a university project. Even to ask would have felt like an exploitation of their trust. Further, apart from these daily digital interactions, I also accompanied my partner through several moments of coping with loss from afar, including attending funerals via videocalls. While being emotionally invested in these situations, at the same time, I noticed that I could but help but to perceive these moments linked to the class discussions of the meaning of digitality. Even though I did not consciously choose to do so, I frequently experienced moments of – hugh, so this is what this feels like – as of recognising myself and others in certain categories and concepts discussed in class. Even though this consciousness might have enabled me to understand - and also cope with - certain situations better, I constantly hated myself for analysing these moments in relation to what I was writing about at the time. It felt like an exploitation of not only of the very personal experiences of my loved ones but also like I was robbing myself of that same experience by pre-examining how it might connect and hence become useful for my studies. I wish I could end this paragraph on a good note – on how I managed to overcome these feelings, but the truth is that I did not. In a way, the light right under Schwartz-Shea and Yanow’s streetlamp at some point just felt too hot, whereby I did not widen the circles due to finding clues for where to look next (2012, 29ff) but because of avoiding specific light spots which I simply did not manage to make sense of in time.

Third and lastly, in the course of first data generation attempts it became inevitably obvious that I could not shake off an overtly present good guys bias myself. During the past two years, a lot of people whose supportive view towards downplaying statements about the COVID-19 virus and the present Brazilian federal government had surprised me, simply changed their minds. It was even hard to tell where they had drawn the line for their support, as many suddenly did not even seem to remember ever having thought otherwise. This again left me in a very like-minded bubble and therefore limited the capacities of negotiating access to arenas where crisis claims would be contested. I hence again was left with what I from my positioned point of view perceived as the good guys which made me feel like I was missing out an important part of the story.

3. (OTHER) WAYS INTO THE FIELD: ON THE QUEST FOR THICK DATA

Building on the insights gained from various failures of doing ethnographic fieldwork in pandemic times, I started to turn my attention to quantitative options of gathering data. In particular, social media and its role in connecting global and local spheres became a promising alternative for finding (other) ways to the field. When realising that my initial ideas of finding ways to my field would run into access, ethical, as well as feasibility concerns that were simply not possible to overcome within the timely constraints and the limited resources of an MA project, I once again reassessed the possible entry points for constructing my field and finally turned my eye to another spot within reach: Social media networks. I became attentive to the political communication taking place on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, but also began to reflect how I, myself engaged with these contents as well as the variety of responds from other national as well as non-state actors interacting with but also contesting certain narratives through collective storytelling, practically grouped by using one the most famous digital characters of the 21st century: The hashtag. Following Cultural Studies professor Andreas Bernard’s elaborations in his Theory of the Hashtag (2018), the sign can be analysed as a social symbol as it “represent[s] a pledge – a pledge to be seen, find an audience, and pool interests” (Bernard 2018, 3). In line with other recent writings, Bernard therefore contends that in the realm of interactive media networks, the hashtag hence has more than a mere functional significance as it does for instance on the dial plate of a telephone (ibid., 26), but also contains the power to convey meaning in a context and therefore contains a high potential for power and politics (Rambukkana 2015, 4).

Now, when turning one’s focus to soial media networks and the use of hashtags for mapping out political narratives, it seems close to inevitable to address the role of Big Data and how such necessarily quantifying approaches fit into the projects’ proclaimed interpretivist logic of inquiry. To reconcile these – as I argue, only at first sight – counter running seeming approaches, I draw on the idea of augmented empiricism (Hsu 2014)and its potential to provide contextual insight that consists of what Tricia Wang has called thick data (Wang 2013). In her contribution, Wendy F. Hsu points to the potential of Big Data and data-driven methods to deepen ethnographic practices (Hsu 2014, 45) by challenging the predominant role of quantitative data approaches as mere tools to extract “information that either supports or disproves hypotheses” within a positivist ideology that produces what Hsu terms disciplined data (Hsu 2014, 50). Instead of merely disciplined data, Hsu contends, we should pay closer attention to generative data which only emerges through the engagement and interpretive eye of an engaged researcher (ibid., 44). As data-driven methods present a valuable asset for “calculating and reframing information” and hence “scrutinize the relationship between micro and macro-observations”, they bear the capacity of scalability which can help the researcher to later zoom in and out and identify relations between different sites and agencies (ibid., 44). How these relations play out in practice, however, and – hence – what contextual meanings are to be explored in between these patterns, requires the positioned interpretation of a human researcher and amounts to what Hsu denotes as inter- or multimodality (ibid., 44). Combining the two capacities of scalability and inter/multi-modality now presents what Hsu calls augmented empiricism, as a “form of immersion” in the digital and hence a promising path towards uncovering contextual meaning-making processes within large data sets (ibid., 44).

The resulting insights amount to what sociologist Tricia Wang with reference to Clifford Geertz has described as thick data which she understands as “ethnographic approaches that uncover the meaning behind Big Data visualization and analysis” (Wang 2013). Wang’s contribution has since inspired a range of methodological debates on interpretive approaches involving the digital realm, especially concerning the value of computational methods for ethnographic practices (Fortun, Fortun and Marcus 2017), the importance of ethics in the datafication of future Anthropology (Pink and Lanzeni 2018) and also further exploration in the search of meaning through digital data (Tromble 2019).

Following Hsu’s idea of augmented empiricism and Wang’s perspective that “Big Data delivers numbers; thick data delivers stories”, I put these methodological suggestions to work within my MA thesis by drawing on Big Data and data-driven approaches with a practice-oriented ethnographic sensibility in order to find ways to my field and make engagements with the contextual meanings of crisis through digital means observable. An endeavour which I will now lay out in detail below.

4. FOLLOW THE HASHTAG: A MULTI-SITED PRAXIOGRAPHY OF GLOBAL

CRISIS THROUGH DATA-DRIVEN METHODS

To generate such “thick data” (Wang 2013) I combined three approaches for the methodical operationalisation of my framework: First, George E. Marcus’ multi-sited ethnography and the idea of of “following” (Marcus 1995, 99, 105-113), second, taking a practice-driven approach to making crisis observable through the research technique of praxiography (Bueger and Gadinger 2018, 29, 131), and third, applying these ideas through the means of data-driven methods.

First, The idea of multi-sited ethnography is closely related to questions arising from globalisation theory throughout the 1990’s, which became particularly important for a major shift in migration studies from merely looking at why people leave their country of origin and settle down somewhere else towards how social relations and identities are maintained in between as transnational phenomena (Marcus 1995, 104f). Throughout lively debates on the role of methodological nationalisms in approaching these transforming processes (Wimmer and Schiller 2003), new concepts emerged – like trans- or plurilocality which sought to capture the importance of local processes and its previously underestimated potential for meaningfully affecting structures transcending national[3] but also global spheres (Robertson 1994; Anghel, et al. 2008; Roudometof 2015). The allocation of previously overlooked sites, where these glocal (Robertson 1994)phenomena are produced, hence became a main concern for ethnographers at the turn of the millennium. A quest which only intensified with the technological advancements and the emergence of the digital as another sphere to consider when addressing pluri/trans- or potentially glocal concerns in the construction of social spaces, relations, and identities (Sigismondi 2012). In Marcus’ frequently cited contribution to this debate (1995), he challenges the until then conventional understanding of ethnographic fieldwork as demanding the researcher to immerse with her field of study for as long as it takes for her to grasp and accurately (re)present the natives’ point of view[4] to her academic peers. Instead, Marcus suggests that the capacity for mobility of the researcher holds a potential for knowledge generation in itself, as he defines the global as “an emergent dimension of arguing about the connection among sites“ a new sphere that could only be grasped by a multi-sited approach to ethnography (Marcus 1995, 99). As this approach bares challenges for the understanding and construction of the field, he proposes the research technique of following as of allocating a constant like people, material things, metaphors, stories, biographies, or reoccurring conflicts which can be traced across a variety of contexts and hence allows the researcher to approach meaningful connections between multiple possible sites (ibid., 97, 105-113). For my MA thesis, I put Marcus’ strategy to use by following hashtags throughout their clusters and thereby allocated possible entry points to my field.

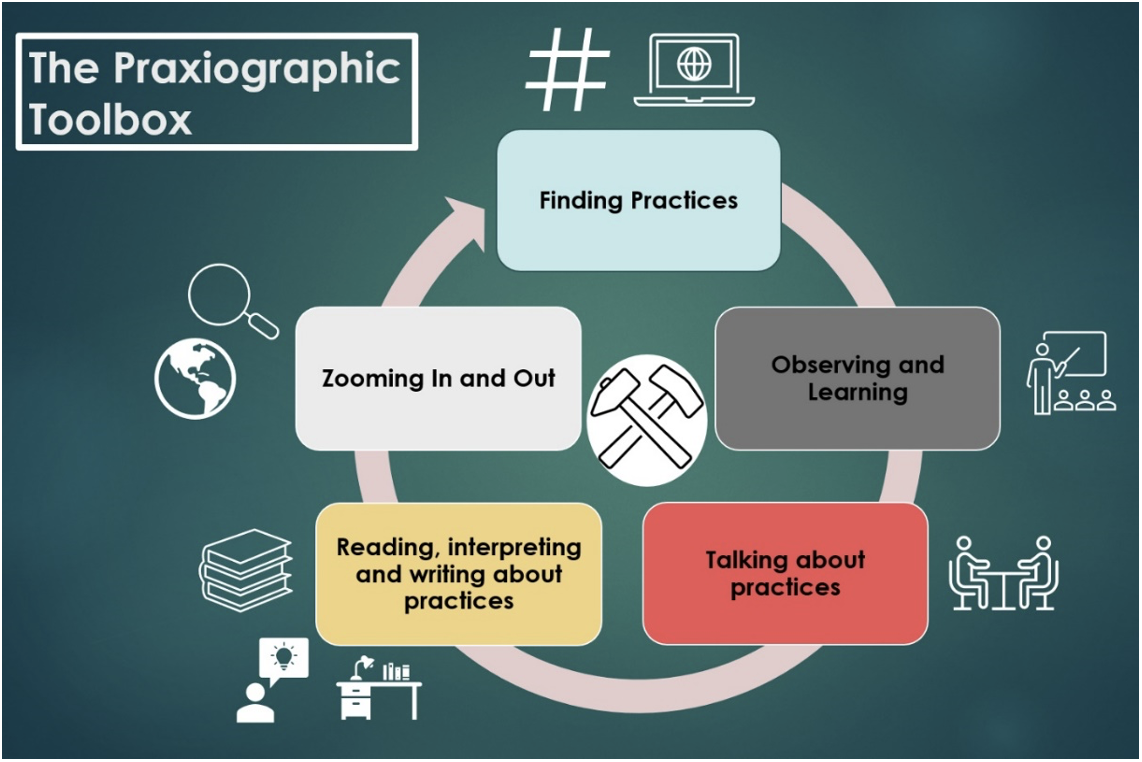

Second, I draw on the research strategy of praxiography – a term coined by Annemol (Mol 2002) and further developed by Bueger and Gadinger (Bueger 2014; Bueger and Gadinger 2018) in an attempt to further discussions on the status of theory and its relations with the practice of doing research itself (Bueger and Gadinger 2018, 133-138). With a clear preference for ethnographic methods like participant observation as of observing and learning practices, praxiographers value the importance of immersion with one’s field of study. Combined with other common qualitative research techniques like interviews and text analysis they also include talking about, interpreting, and lastly writing about practices in the toolbox (Bueger and Gadinger 2018, 143).

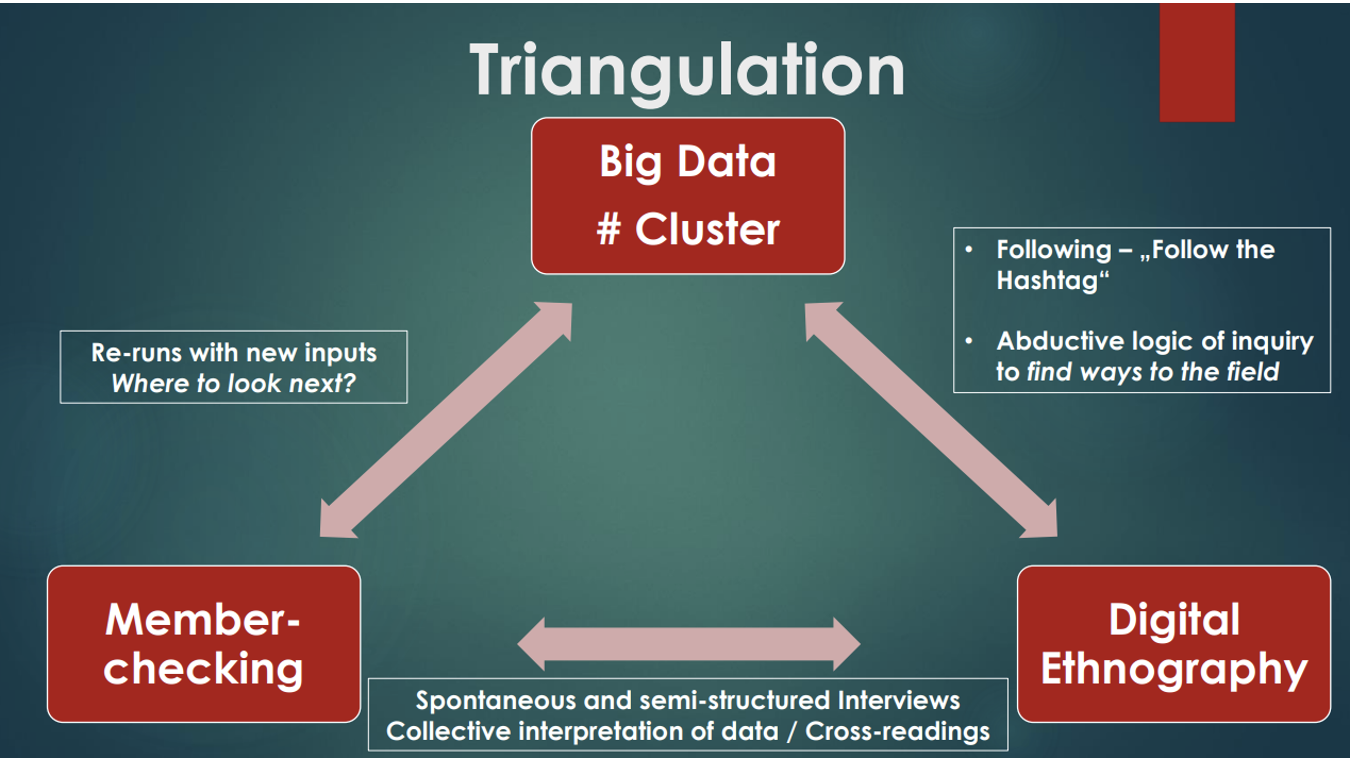

Third, let me then lay out the final methodical tools that played a part in generating thick data (Wang 2013)during the COVID-19 pandemic in and beyond Brazil in praxiographic terms: Namely, (a) finding practices through the examination of social media platforms with a focus on the mappings of hashtag clusters and social media networks (Bernard 2018) through an abductive logic of inquiry; (b) observing and learning practices through Digital Ethnography (Pink, Horst, et al. 2016); (c) talking about practices in spontaneous, informal, as well as semi-structured interviews; and lastly, as in (d) reading, interpreting, and writing about practices.

Figure 1: The Praxiographic Toolbox (own Illustration)

Figure 1: The Praxiographic Toolbox (own Illustration)

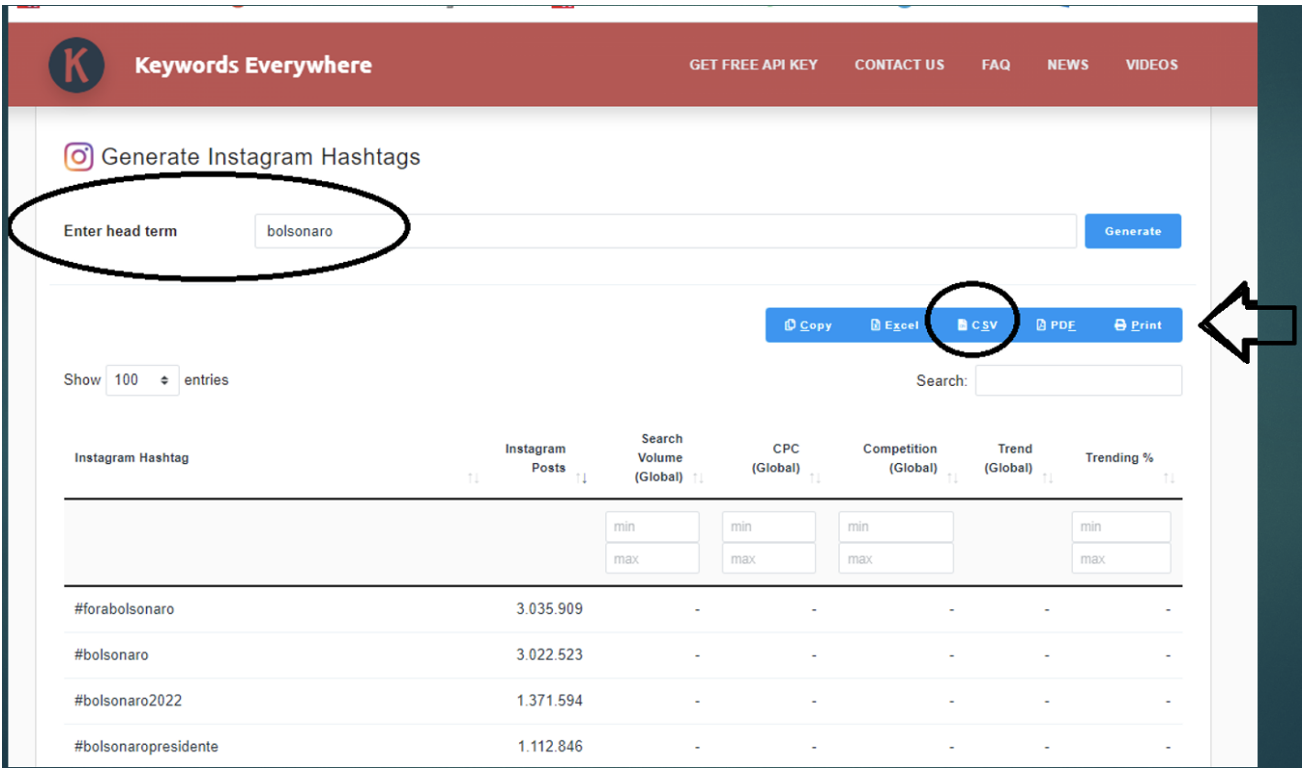

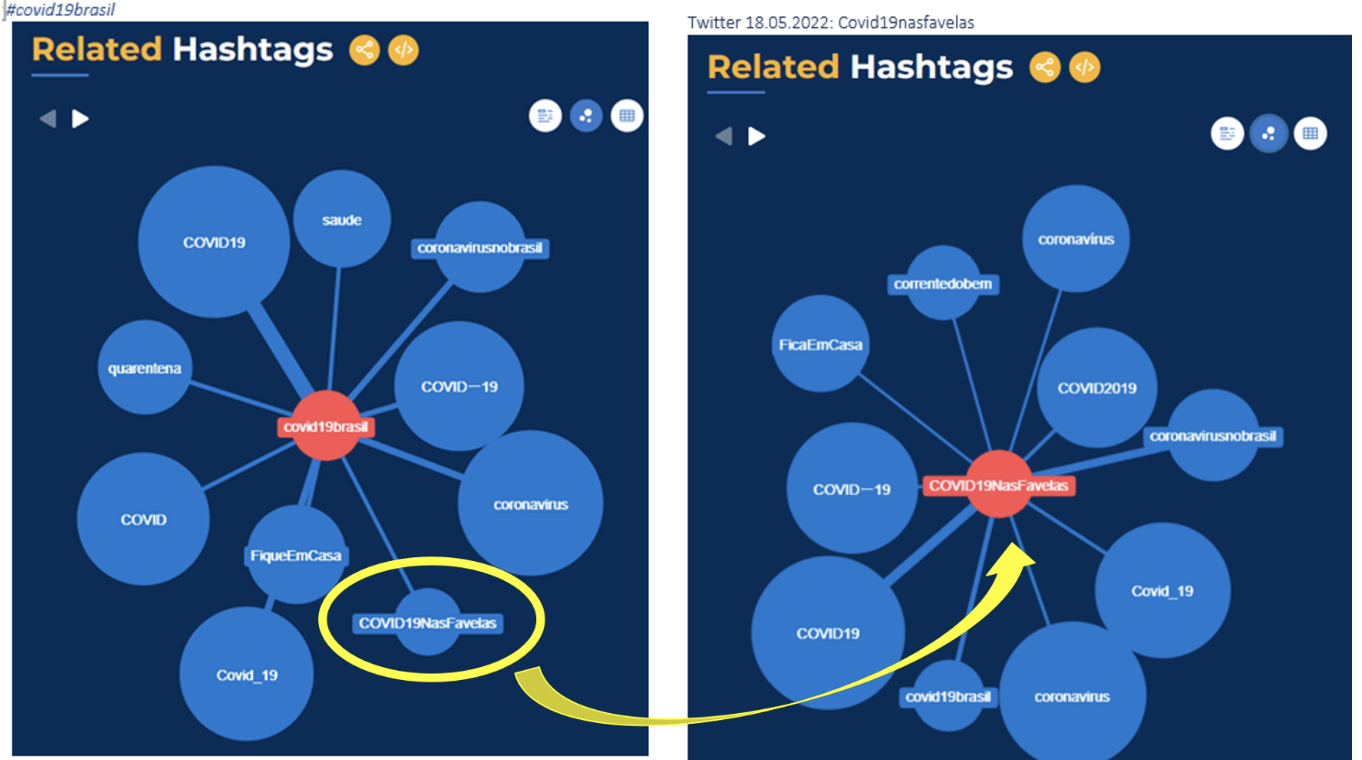

- The first move consisted in finding practices to engage with. Due to the practical challenges discussed above, I retrieved my initial data sets from the free trial versions of the Google Chrome extension Keywords Everywhere and the online service Hashtagify.me to identify the most used hashtags according to a list of keywords and then analyse the networks of the resulting hashtags to other related topics on Twitter and Instagram. For Facebook, where the hashtag groupings do not work the same, I drew on a mix of platform specific analytical tools and immersion techniques like a digital ethnographic trip ‘down the rabbit hole’.

Importantly, I draw on Big Data analysis tools in order to find ways to my field. I am hence not conducting a full network analysis of the hashtags found (Highfield 2015; van Haperen, Nicholls and Uiter 2018; Pournaki, et al. 2021;), but instead engage with them through an abductive logic of inquiry as of following their interconnections across the chosen platforms. In doing so, I always stay open to how one cluster, content or link might lead me where to look next (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow, 2012, 29ff). While I kept a systematic record of my proceedings (Annex_b), I take the insights I found through the help of digital methods still as carriers of meaning in themselves and continiously triangulated them with further ethnographic/praxiographic techniques, especially in the sense of talking about them with informants but also cross-checking them with other media sources and recent academic analyses on the issue. Due to some pecularities of the different platforms, I quickly lay out my proceedings when finding ways to my field on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook below:

Instagram: I started by conducting a keyword search using the free version of the Google Chrome extension Keywords Everywhere which displays the hashtags used on the platform related to the search term as well as how often they have been used in a feed post. From there, I took the top 5 Instagram hashtags of each keyword and created a word cloud of those tags in relation to the initial search term via the online service Hashtagify.me.

Figure 2: Screenshot from a keyword search on the add-on "keywords everywhere" (retrieved 04/22/2022)

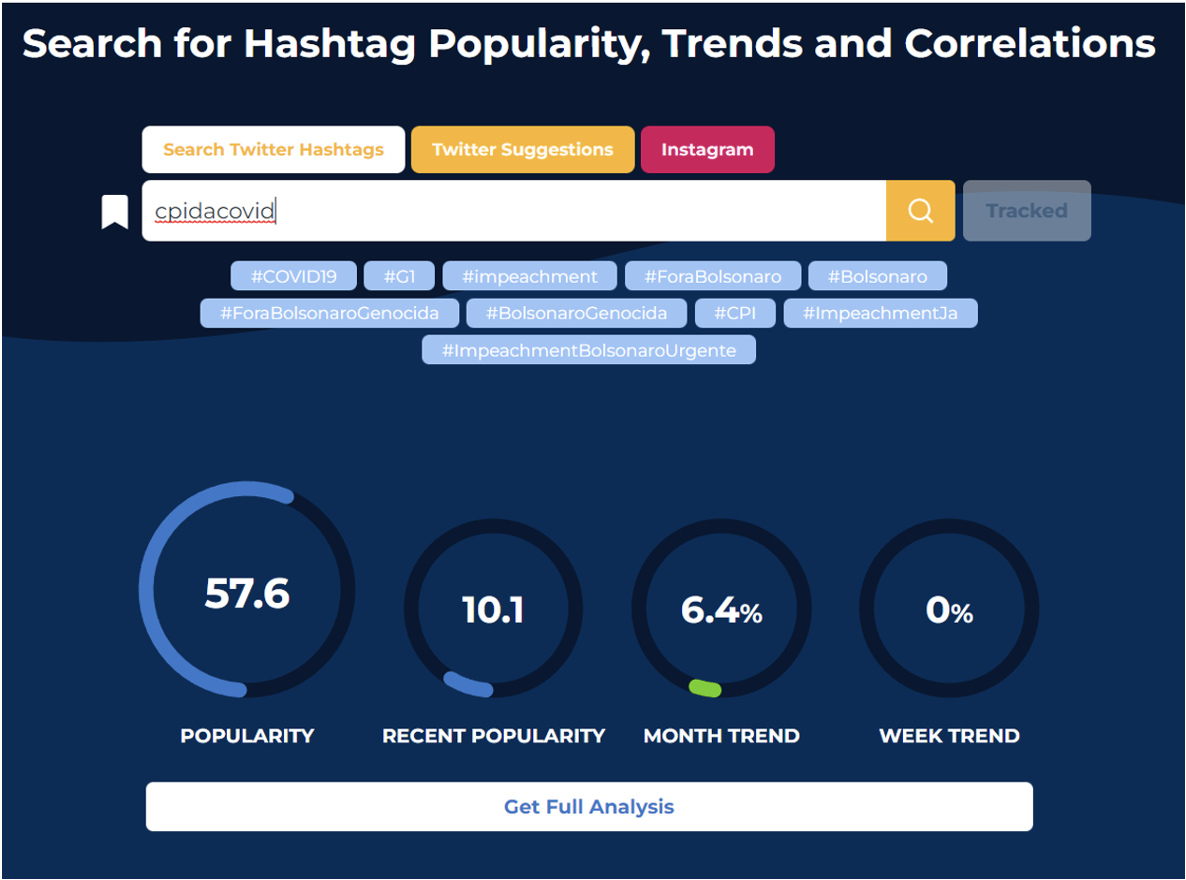

Twitter: Next, I conducted the same keyword search for Twitter through the online service Hashtagify.me, and also took the top 5 Instagram hashtags of each search word retrieved before to cross-check for possible variation between the platforms. I then created visual network mappings and word clouds to display further topics and hashtags related to the initial search term. Further, I used the Twitter API Timeline Explorer – which shows the top 10 topics from the last 500 tweets a specific user has posted on the timeline (Twitter API V2 Timeline Explorer 2022) – to explore the importance the related topics were given compared to the general contend of those Twitter accounts that seemed most active and influential in the online debates based on their general reach.

Figure 3: Screenshot from the online service "Hashtagify.me" (retrieved 06/05/2022

Facebook: For the Facebook platform, where the use of hashtags does not work in the same way, I examined official government accounts which stood out as most involved on Twitter and Instagram as well as fan pages related to Brazilian politics perspectives. Further, I made use of research tools provided by Meta like FORT, Data for Good and applied for a CrowdTangle access (research.facebook.com 2022).I started my search by introducing relatively neutral keywords in English and Portuguese spelling like Brasil/Brazil, crisis/crise; crise mundial/global from where I quickly found frequent references to related hashtags like #COVID19; #COVID19brasil; #Brazil.Below I listed some examples of the main search rounds I conducted whose full logging is laid out in the Annex document b (Annex_b). From there on, I searched for content on the chosen platforms, related to those hashtags and in doing so, sought to continuously widen the circles and cross-checking my impressions with further readings, in interviews and through comparisons with official government accounts (see Figure 4 on abductive and recursive proceeding and Figure 5 on triangulation).

Figure 4: Exemplary screenshots of abductive proceeding when following the hashtag of #Covid19Brasil (Retrieved 05/18/2022)

Figure 5: Triangulation aimed at for the study (own illustration) -

observing and learning practices became possible through the use of various ethnographic methods which adhere to Pink et al.’s idea of Digital Ethnography:

Participant Observation: Besides constantly monitoring and reflecting my own uses of social media channels concerning the topic through my everyday use of the platforms, I additionally created two separate new accounts in order to immerse in my digital field on the facebook platform. In doing so, I started to go down the rabbit hole on each of the two most counter running narratives of the keywords “fora Bolsonaro”[Bolsonaro out] and “fecha com Bolsonaro” [expression of voter’s support for Bolsonaro] which I identified through the hashtag clusters derived from Instagram and Twitter as well as drawing on data of an additional sentiment analysis through Hashtagify.me.

Event Observation: As the notion of event observation in the digital realm can get a little blurry due to the available option of assisting a range of events not only from afar but time-delayed through recordings, I find it important to state that in the case of this MA thesis I will count both as such; live-streamed transmissions of protests, congress hearings, or also instalives[5] during which I was taking fieldnotes, on the one side, but also assisting their recordings subsequently on the other.

Accidental Ethnography and Reflexivity: I made use of what has been termed accidental ethnography(Poulos 2009; Fujii 2015) as of “turning unplanned moments in the field into data” (Fujii 2015, 525), hence reconstructing meaningful linkages to my topic of interest retrospectively. In order make sense of my own positionalities within the topic, I drew on separately written field documents as of fieldnotes (Wolfinger 2002)which exclusively dealt with data related to the research topic on the one side, and a research diary in which I constantly reflected on my own trajectories throughout the whole research process, including moments of failing in the field as laid out in the sub-section 3.1.3. - Understanding Interviews in the broad praxiographic definition of talking about practices (Bueger and Gadinger 2018, 143), I will only distinguish here between spontaneous, unstructured, and semi-structured interviews which all helped me to make sense of the topic in question. Importantly, contrary to conventional interview techniques and consistent with the interpretive research logic this MA thesis applies, I adhere to what Lee Ann Fujii has called a relational approach (2018) to interviewing which pays particular attention to the value of reflexivity and does not seek to “extract” information from the interviewee, but instead wants “to learn how they make sense of the world by engaging them in dialogue”, wherefore “data emerge[s] from interaction, rather than interrogation.” (Fujii 2018, 8). Following traditions of Narrative Theory [Erzähltheorie] (Schütze 1976; Rosenthal 2017; 2018), Fuji largely builds her approach on the role of interviewees as the narrators of their own storytelling, as she aptly puts it: “Through the stories they tell, people locate themselves as agents in the various social worlds they identify with, aspire to, imagine, or inhabit. People’s stories provide insight into why they think certain events happened one way and not another” (Fujii 2018, 3).

I sought to engage with people’s stories through spontaneous interviews as of interactions during or after which I perceived a connection to the topic of this MA thesis, and which gave me the impression of better understanding a certain aspect of it. Or, differently put: Unplanned moments in the field (Fujii 2018, 3) in which I felt a sense of sense-making in a particular contextual setting related to my research project. By unstructured, unrecorded interviews I characterise encounters in which I did seek an exchange to intentionally talk about the topic of my MA thesis and ask for the other person’s opinion, interpretation or statement on a specific topic or request their feedback on my own interpretations of specific aspects.

I also conducted one semi-structured and recorded interview which took place via zoom. I designed a list of possible questions beforehand which were sent to the interviewee a few days before (Annex_d, 3). I also asked my interviewee to sign a consent form (see Annex_d, 2) whose contents I drew on again at the start of the interview to ensure that my conversation partner had understood what the study was about, how their data would be used as well as what measures I was taking to ensure that the given information would stay anonymised and protected. At the end, I planned 15 to 30 minutes to evaluate how the participant felt during the exchange, particularly how the circumstance of the talk taking place digitally on zoom was perceived and to ask if my interview partner would have any question for me. The interview was conducted in the interviewees’ native language, Portuguese, and later transcribed with the help of the automated transcription feature from Microsoft Word 365. I provided a copy of the respective transcript and will also send the final written text to the interviewee. To conduct what Schwartz-Shea and Yanow have called “Member-checking” (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 106), I contacted my interviewee via Whatsapp when drawing on passages from our exchange in my thesis and ask her for feedback on my triangulation with other sources. - Lastly, as of reading, interpreting and writing about practices as essential but often underestimated parts of doing research, I would like to argue for taking the constant going back and forth between theory and data (Kurowska and de Guevara 2020, 1215; Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 26) from which the sensitising concepts (Blumer 1954), laid out throughout chapter 2, emerged, as a crucial part of the methodical toolbox of this MA thesis as well. Reading about practices, in this regard, consisted mostly in the study of news articles and academic papers on the issue, which I recursively sought to put in relation with the information from official government websites and content from social media accounts. The resulting interpretations, then, were triangulated in instances of talking about practices as of bringing up the issues in interviews as well as spontaneous encounters. In doing so, data protection and ethical issues concerning the use of digital content and methods for research were being carefully considered and ensured in the presentation of the insights throughout chapter 4 (Boellstorff, Nardi and Taylor 2012; Pink and Lanzeni 2018) Lastly, the constant reflection processes through zooming in and out (Wiener 2007; Nicolini 2009; Bueger and Gadinger 2014; 2018) on my empirical findings as well as on linkages between theory and practice only came into being when writing about them. These meaning-making processes taking place at the final stage of research when writing up one’s findings, are often portrayed as the moment of eloquently ordering the messes we have found in the field into a presentable argument for the reader and thereby miss a very crucial component – the messiness of deskwork. Yet, after all, it is this last practice of making sense of what one seeks to generate knowledge about that, after all, determines either the success or failure of the entire research process by grading its written end product – hence, why not grant it the attention it deserves? Namely as another crucial component of making sense of the puzzle at hand itself. Thereby directly following Bueger himself who encourages his readers to “be open to surprise and the actual messiness of practice” (Bueger 2017, 131).

5. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS: POTENTIALS AND PITFALLS OF AN INVOLUNTARY

TURN TO THE DIGITAL IN PANDEMIC TIMES

Throughout this working paper, I reflexively engaged with the fact that during the time of its making, the research process of my MA dissertation became inevitably impacted by the same global crisis it was seeking to generate knowledge about when lockdown and travel restrictions made plans for fieldwork, initially planned as an on-site research stay in Brazil, infeasible. This involuntary turn to the digital, however, turned out to hold a wide range of surprising possibilities and presented an opportunity to engage with the commitment of an abductive research logic in depth as of letting oneself be “carried away” by surprises in the field (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 30f). In doing so, I came to value the messiness of research as a practice (Bueger 2017, 131) and explored new methodological pathways through the use of Digital Ethnography (Pink, Horst, et al. 2016) and data-driven methods to find (other) ways to my field. In particular, through the help of Big Data sources, I was able to unpack a praxiographic toolbox as of first, finding practices through the examination of hashtag clusters across social media platforms to then triangulate these insights along Bueger and Gadinger’s recommendations (Bueger and Gadinger 2018, 143) with immersion and observation techniques (observing and learning practices), insights from spontaneous and semi-structured interviews (talking about practices) as well as constantly moving back and forth between theory, data and my interpretations (Kurowska and de Guevara 2020, 1215; Schwartz-Shea and Yanow 2012, 26) (reading, interpreting and writing about practices).

Yet, one might still ask: Was the digital a second choice after all? In the light of my repeatedly pledged commitment to an abductive logic of inquiry I now quite firmly respond: Yes, of course it was! And most importantly: What else did you expect? Where would be the fun in it when closing the books after ones’ first hunch on the puzzle? Confronted with a variety of challenges, reaching from unusual starting conditions, encountering difficulties of securing funding, and finally reaching agreement between feasibility, access- and ethical concerns, it turned out that the hardest part of doing research was to establish a sustainable frame and a secure work environment to get started in the first place. Once we had that done the digital component led to the same conclusion, we probably had reached without it: Namely, that there are no first choices when wanting to conduct meaningful research. Committing to an interpretive-ethnographic sensibility meant the same for incorporating the digital realm than it would have had without it: to keep looking until the semesterly deadlines and the requirement of a written product of my research endeavor would put an end to it. And consequently, that is exactly what I did.

However, while this working paper has focused on the designing process of doing research from the home-office, follow up analyses on the potentials but also limits of the actual interpretation of the data in my MA thesis would definitely be fruitful in order to engage more deeply with questions of the role of online/offline settings play in the generation of knowledge. For instance, while the involuntary turn to the digital has presented an opportunity for abduction to unfold along the methodical operationalisation of the study, the triangulation with the findings generated through data-driven methods still showed the importance of a cautious awareness of digitality as a site of study which is “constantly mediated” (Pink et. Al 2016, 3) and necessarily restrains the researcher in decisions of where to turn her eye and commit her attention to. This concerns, for example, implications of what the difference in not only not being there but also not being then(Postill 2017) entailed when examining data retrospectively. When taking the ideas of an interpretive approach to the digital further, the importance of detecting omissions as of paying close attention to what we cannot see – hence should remain a crucial part of one’s methodological considerations. Particularly, they point out the importance of constantly taking online/offline entanglements into account when trying to generate “thick data” (Wang 2013). I therefore do see potential in cross-examinations of the use of Big Data sources for finding ways to a field to which presential access is not possible, yet a careful triangulation with other sources of data is still crucial in order to bring implicit knowledges between online/offline practices to the fore.

For the sake of workability and the given provisions, I will confine the scope to the design of the data-driven methods approach for now. Yet, building on the insights from the in-depth methodical discussion laid out in this working paper, I would be keen on taking these ideas further as of reflecting on its use in a specific context, as I have done in my MA dissertation (Gresz 2022c), and engage in more profound discussions on its use for future projects.

6. REFERENCES

Abidin, Crystal and Gabriele de Seta (2020): „Private Messages from the Field: Confessions on Digital Ethnography and Its Discomforts.“ Journal of DigitalSocial Research, No.1. Vol.2: 1-19.

Anghel, Remus Gabriel/ Gerharz, Eva/ Rescher, Gilberto/ Salzbrunn, Monika (2008. „Introduction: The Making of World Society.“ In The Making of World Society: Perspectives from Transnational Research, edited by Remus Gabriel Anghel, Eva Gerharz, Gilberto Rescher and Monika Salzbrunn, 11-21. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Bernard, Andreas (2018): Theory of the Hashtag. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag.

Beyond Borders e.V. / Projekte (2022): „Beyond Borders e.V.“ beyond-borders-ev.de. URL: https://beyond-borders-ev.de/de/projects/ Retrieved 07/09/2022.

Bliesemann de Guevara, Berit/ Kurowska, Xymena (2020): „Building on Ruins or Patching up the Possible? Reinscribing Fieldwork Failure in IR as a Productive Rupture.“ In Fieldwork as Failure: Living and Knowing in the Field of International Relations, edited by Katarina Kušić and Jakub Záhora [eds], 163-174. Bristol: E-International Relations.

Blumer, Herbert (1954): „What Is Wrong with Social Theory?“ American Sociological Review, 19. (1): 3-10.

Boellstorff, Tom (2008): Coming of age in Second-Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Boellstorff, Tom/ Nardi, Bonnie/ Pearce, Celia/ Taylor, T.L. : (2012): „Chapter 8. Ethics Participant Observation in Virtual Worlds.“ In Ethnography and Virtual Worlds, edited by Tom Boellstorff, Bonnie Nardi and Celia Pearce, 129-150. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bueger, Christian (2017): „Practices, Norms, and the Theory of Contestation.“ Polity, No. 1. Vol. 49: 126-131.

— (2014): „Pathways to practice: praxiography and international politics.“ European Political Science Review, 6:3: 383 – 406.

Bueger, Christian/ Gadinger, Frank (2018): International Practice Theory: New Perspectives (Second Edition). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

— (2014): International Practice Theory: New Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Burawoy, Michael (2001): „Manufacturing the Global.“ Ethnography, (2). Vol 2: 147-159.

Burns, Tracey/ Gottschalk, Francesca (2020): Education in the Digital Age:. Paris: Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing.

Cocco, Chiara. (03/26/2020) „Ethnographic Research in the Time of Coronavirus.“ transformations-blog.com.URL: http://transformations-blog.com/ethnographic-research-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/ Retrieved 07/18/2022.

Coleman, Gabriella (2010): „Ethnographic approaches to digital media.“ Annual Review of Anthropology, 39: 1-19.

Fortun, Mike/ Fortun, Kim/ Marcus, George E. (2017): „Computers in/and Athropology: The Poetics and Politics of Digitization.“ In The Routledge Compagnion to Digital Ethnography, edited by Larissa, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell [Ed.] Hjorth, 11-20. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian (2019): „What Is Critical Digital Social Research? Five Reflections on The Study of Digital Society.“ Journal of Digital Social Research, No.1. Vol.1: 10-16.

Fujii, Lee Ann (2018): Interviewing in social science research: a relational approach. New York: Routledge.

— (2015): „Five stories of accidental ethnography: turning unplanned moments in the field into data.“ Qualitative Research, 15(4): 525-539.

Geertz, Clifford (1974): „"From the Native's Point of View": On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding.“ Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Vol. 28, No. 1. October: 26-45.

— (1973): The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Gresz, Verena. (2022a. „Field Notes“, May 2020 – May 2022, Hamburg, University of Hamburg, 2022a

— (2022b.): „Research Diary“, May 2020 – May 2022, Hamburg, University of Hamburg, 2022b

— (2022c.) “The Practices of Crisis Denial in Global Politics: A Digital Ethnography of the (Un)Making of Urgency during the COVID-19 Pandemic in and beyond Brazil”. MA thesis handed in for the course of study of Latin American Studies M.A. at the University of Hamburg (UHH), June 2022.

— (2021): „Das digitale Kapital der Soziologie: Eine ketzerische Auseinandersetzung mit Bourdieus Homo Academicus während der COVID-19 Pandemie“ Term paper for the seminar Introduction to sociological thinking conducted by Dr. Gilberto Rescher throughout the winter term 2020/21 at the University of Hamburg (UHH)

Guzzini, Stefano (2000): „A Reconstruction of Constructivism in International Relations.“ European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 6(2). June: 147–182.

Highfield, Tim (2015): „A methodology for mapping Instagram hashtags.“ First Monday, 01. January: 1-14.

Hsu, Wendy F. (2017): „A Performative Digital Ethnography: Data, Design, and Speculation.“ In The Routledge Compagnion to Digital Ethnography, edited by Larissa, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell [Ed.] Hjorth, 40-50. New York: Routledge.

— (2014): „Digital Ethnography Toward Augmented Empiricism: A New Methodological Framework.“ Journal of Digital Humanities, 1. 3: 43-64.

Jackson, Patrick Thaddeus (2011): The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. New York: Routledge.

Kurowska, Xymena/ Bliesemann de Guevara, Berit (2020): „Interpretive Approaches in Political Science and International Relations.“ In The Sage Handbook of Research Methods in Political Science, edited by Luigi Curini and Robert Franzese, 1211-1230. Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne: Sage.

Kušić, Katarina/ Záhora, Jakub (2020): „Introduction: Fieldwork, Failure, IR.“ In Fieldwork as Failure: Living and Knowing in the Field of International Relations, edited by Katarina and Jakub Záhora [ed.] Kušić, 1-16. Bristol: E-International Relations.

Lynch , Cecelia. (2014): Interpreting International Politics. New York; London: Routledge.

Marcus, George E. (1995): „Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.“ Annual Review of Anthropology, 24: 95-117.

Marres, Noortje (2017): Digital Sociology: The Reinvention of Social Research. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Miller, Daniel (2018): „Digital Anthropology.“ The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. edited by Felix Stein, Matei Candea, Sian Lazar, Hildegard Diemberger, Joel Robbins, Rupert Stasch, and Andrew . URL: https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/printpdf/462 Retrieved 07/18/2022.

Mol, Annemarie (2010): „Actor-Network Theory: Sensitive Terms and Enduring Tensions.“ Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie and Sozialpsychologie, 1. 50: 253–269.

— (2002): The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Olson, Gary A. (1991): „Clifford Geertz on Ethnography and Social Construction.“ Journal of Advanced Composition (JAC) [digital.library.unt.edu]. 11(2). Winter. URL: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc40372 Retrieved 06/03/2022.

Pereira, Gabriel/ Bueno Bojczuk Camargo, Iago/ Parks, Lisa (2022): „WhatsApp disruptions in Brazil: A content analysis of user and news media responses, 2015–2018.“ Global Media and Communication, 18(1): 113-148.

Pink, Sarah (2019): „Digital Social Future Research.“ Journal of Digital Social Research, No.1. Vol.1: 41-48.

— (2012): Situating EverydayLife: Practices and Places. London: Sage.

Pink, Sarah/ Horst, Heather A./ Postill, John/ Hjorth, Larissa/ Lewis, Tania/ Tacchi, Jo (2016): Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. Los Angeles: CA: Sage.

Pink, Sarah/ Lanzeni, Debora (2018): „Future Anthropology Ethics and Datafication: Temporality and Responsibility in Research.“ Social Media + Society, April-June: 1-9.

Plümper, Thomas (2012): Effizient schreiben : Leitfaden zum Verfassen edited by Qualifizierungsarbeiten and wissenschaftlichen Texten. München: Oldenbourg Verlag.

Plan International Deutschland e.V. (2022): „Plan International Deutschland e.V.“ plan.de. URL: https://www.plan.de/ Retrieved 07/09/2022.

Postill, John (2017): „Remote Ethnography: Studying Culture from Afar.“ In The Routledge Compagnion to Digital Ethnography, edited by Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell, eds Larissa, 61-69. New York: Routledge.

Pouliot, Vincent (2008): „The Logic of Practicality: A Theory of Practice of Security Communities.“ International Organization, 2. 62: 257–288.

Poulos, Christopher N. (2009): Accidental Ethnography: An Inquiry into Family Secrecy. New York: Routledge.

Pournaki, Armin/ Gaisbauer, Felix/ Banisch, Sven/ Olbrich, Eckehard (2021): „The Twitter Explorer: A Framework for Observing Twitter Through Interative Networks.“ Journal of Digital Social Research, VOL. 3, NO. 1: 106–118.

Rambukkana, Nathan (2015): HASHTAG PUBLICS: The Power of Discursive Networks . New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Rescher, Gilberto (2018): Doing Democracy in indigenen Gemeinschaften: Politischer Wandel in Zentralmexiko zwischen Transnationalität and Lokalität. Bielefeld: transcript.

Roudometof, Victor (2015): „Theorizing glocalization: Three interpretations.“ European Journal of Social Theory, 1–18.

Schmidt, Robert (2017): „Sociology of Social Practices: Theory or Modus Operandi of Empirical Research?“ In Methodological Reflections on Practice Oriented Theories, edited by Beate Littig, and Angela Wroblewski, eds. Michael Jonas, 3–17. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Schnegg, Michael (2019): „The Life of Winds: Knowing the Namibian Weather from Someplace and from Noplace.“ American Anthropologist, no. 4 . 121.

Schwartz-Shea, Peregrine/ Yanow, Dvora (2012): Interpretive Research Design: Concepts and Processes.New York: Routledge.

Shiffman, Naomi/ Silverman, Brandon/ [Meta] (2020): „CrowdTangle opens public application for academics.“ research.facebook.com. 31. 08. URL: https://research.facebook.com/blog/2020/07/crowdtangle-opens-public-application-for-academics/ Retrieved 06/03/2022.

Shifman, Limor (2013): „Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker.“ Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3): 362–377.

Sigismondi, Paolo (2012): The Digital Glocalization of Entertainment: New Paradigms in the 21st Century Global Mediascape. r. New York: Springer.

Tagesschau (04/24/2021): „Corona-Folgen im Jahr 2020.“ tagesschau.de. URL: https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/coronapandemie-arbeitsmarkt-101.html Retrieved 20.05.2022.

Tromble, Rebekah (2019): „In Search of Meaning: Why We Still Don't Know What Digital Data Represent.“ Journal of Digital Social Research, No.1. Vol.1: 17–24.

Twitter API V2 Timeline Explorer (06/04/2022): „Twitter API V2 Timeline Explorer.“ v2-timeline-explorer.glitch.me. URL: https://v2-timeline-explorer.glitch.me Retrieved 04. 06 2022.

Ungbha Korn, Jenny (2019): „#iftheygunnedmedown: How Ethics, Gender, and Race Intersect when Researching Race and Racism on Tumblr.“ Journal of Digital Social Research, No.1. Vol.1: 41-44.

van Haperen, Sander/ Nicholls, Walter/ Uiter, Justus (2018): „Building protest online: engagement with the digitally networked #not1more protest campaign on Twitter.“ Social Movement Studies, 17:4: 408-423.

Wang, Tricia (05/13/2013): „Big Data Needs Thick Data.“ Ethnography matters. URL: http://ethnographymatters.net/blog/2013/05/13/big-data-needs-thick-data Retrieved 04/28/2022 2022.

Wimmer, Andreas/ Glick, Nina (2003): „Methodological Nationalism, the Social Sciences, and the Study of Migration: An Essay in Historical Epistemology.“ The International Migration Review, Transnational Migration: International Perspectives. Vol. 37, No. 3: 576-610.

Wolbring, Tobias (2020): „The Digital Revolution in the Social Sciences: Five Theses about Big Data and Other Recent Methodological Innovations from an Analytical Sociologist.“ In Soziologie des Digitalen – Digitale Soziologie?, edited by Sabine Maasen and Jan-Hendrik Passoth [Hrsg.], 60-89. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

[1] These insights represent a reconstruction of my own experiences with the digital in the academic realm from a research diary as well as field notes taken since the start of a digital research project in the seminar Interpretive Research Design and Political Ethnography conducted by Dr. Riccarda Flemmer throughout the summer term 2020 at the University of Hamburg which I have kept on writing throughout the course of the working paper’s seminar until today (Gresz 2022a; 2022b).

[2] Further, I also build on thoughts that I elaborated on throughout a course paper titled „Das digitale Kapital der Soziologie: Eine ketzerische Auseinandersetzung mit Bourdieus Homo Academicus während der COVID-19 Pandemie“, handed in for the seminar Introduction to sociological thinking conducted by Dr. Gilberto Rescher throughout the winter term 2020/21 (Gresz 2021).

[3] See here for example the makings „transnational citizenship“ and transforming gender relations in the Valle del Mezquital in México through local community practices (Rescher 2018).

[4] On a critique on this particular point see for example: (Geertz, "From the Native's Point of View": On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding 1974)

[5] The Instalive function is a feature on the Instagram platform for livestreaming videos to assigned followers.